Ministering and the Parables of Jesus

*(the following is a talk I gave in my ward July 25, 2021)* The topic I was invited to speak on is Ministe...

I’ve seen the phrase “Radical Compassion” being used increasingly in conjunction with technology and ethics. I think this is very much needed as we move beyond empirically-driven “Hows?”, “Whys?”, and “Whats?”, which are the necessary drivers of our technological advancements to morally and ethically-driven questions of “How?”, “Why?”, and “Who?”, that necessarily shape our communities and relationships. Because our tools and technologies are increasingly and exponentially capable of transforming the human condition (for good or evil), the role of compassion may prove to be even more important than those tools and technologies themselves.

While it’s hard to pin down new or returning terminologies as they germinate, Khen Lampert offers a definition of “Radical Compassion” in his book Traditions of Compassion: from Religious Duty to Social-Activism:

I have noted that compassion, especially in its radical form, manifests itself as an impulse. This manifestation stands in stark opposition to the underlying premises of the Darwinist theories, which regard the survival instinct as determining human behavior, as well to the Freudian logic of the Pleasure Principle, which refutes any supposedly natural tendency on the part of human beings to act against their own interests and proposes viewing such an inclination as the product of cultural conditioning …”

Lampert examines different models of compassion in different cultures and religions in history. He offers a model of compassion which is presented as a possible antidote to “neocapitalist postmodernism”. It’s interesting that Lampert characterizes compassion as an “impulse” that is not reducible to Darwinism, Freudian logic, or other postmodern ideas. His perspective can support the case that compassion is much more central to the core of what it means to be human and is an independent force far more powerful and necessary than I think we realize.

Mormonism, as a Christ-centered faith, draws it’s most powerful narratives on compassion from the life and teachings of Christ. The Book of Mormon echoes the necessity of charity that the Bible testifies of. In Ether chapter 12 Christ warns that without charity mankind’s destiny with Him will be unattainable:

except men shall have charity they cannot inherit that place which thou hast prepared in the mansions of thy Father

And Moroni writes that charity must be a the center of our identities:

if ye have not charity, ye are nothing, for charity never faileth. Wherefore, cleave unto charity, which is the greatest of all, for all things must fail — But charity is the pure love of Christ, and it endureth forever … pray unto the Father with all the energy of heart, that ye may be filled with this love

Mormon narratives on charity and compassion don’t see those as a mere byproduct of religion but instead as the author of it. Do we allow our faith to be powerfully, even transformatively, lead by compassion? Or do we see compassion as something we pull behind our faith? Do we allow compassion to challenge our beliefs? Or do we challenge compassion with our beliefs?

For me, the most powerful story in the Christian world-view that illustrates the principle of compassion and charity is the Parable of the Good Samaritan told by Christ in the New Testament:

Here, a Samaritan helps a Jew left for dead on a road between Jericho and Jerusalem. This parable is a wonderful pattern of the courage and need for mankind to recognize our shared humanity. But beyond the surface of the parable there’s a deeper lesson when we look at the historical context around the Jewish and Samaritan nations at the time of Jesus.

The history between the Samaritans and Jews is fascinatingly tragic, and we can learn a lot about the intent of Christ’s parable by understanding that. Here are some highlights.

Needless to say, these weren’t just neighbors who didn’t get along. This was an ancient and deeply rooted hatred and disdain for each other that had attached itself to the very identity many had of what it was to be a Jew or Samaritan at that time. It must have pained Jesus to see this rift of hate between the children of Israel. So it’s important to acknowledge that Christ’s choice to make a Samaritan the protagonist of this parable wasn’t a random thought, but instead a divine call for those hearing it to see past what society sees as insurmountable or unfathomable differences and conflicts and instead choose to see each other as fellow neighbors and children of God: a powerful message for our often divided era.

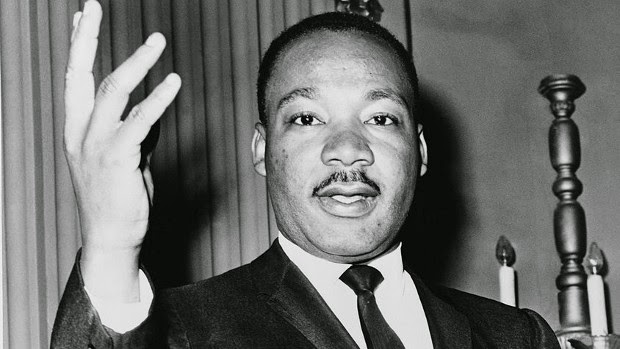

Martin Luther King gave insight on this parable (ironically and tragically) just one day before his assassination, in his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech:

It’s possible that the priest and the Levite looked over that man on the ground and wondered if the robbers were still around. Or it’s possible that they felt that the man on the ground was merely faking, and he was acting like he had been robbed and hurt in order to seize them over there, lure them there for quick and easy seizure. And so the first question that the priest asked, the first question that the Levite asked was, ‘If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?’ But then the Good Samaritan came by, and he reversed the question: ‘If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?’”

I absolutely love this insight here because it gets at the essence of charity and compassion. That they fundamentally change our nature and perspective. Compassion powerfully refutes the kind of political and epistemological tribalism and self-destructive behavior that can be so prevalent today. Going back to Lampert, the powerful impulse illustrated in the protagonist of the Samaritan caused him to overcome both the physical risks and societal risks that loomed over the situation he found himself in. This kind of impulse is a unique tool that can break free of the reductive impulses of self-preservation and cultural norms. Radical indeed!

This kind of charity and compassion may be the source of change that proves essential as mankind begins to wield technologies capable of playing out our greatest aspirations as well as our darkest nightmares; often portrayed in our theatrical fiction and mythologies. Indeed, our ability to cross self-destructive Great Filters which may lie in our future may hinge not on our technological tools but in these impulses of the heart. When facing the great threats and opportunities that can come with technology, it’s important to focus on what we can control. And certainly, as illustrated by the parable of the Good Samaritan, the degree of compassion and charity in our hearts and communities is within our power to control.

But this is hardly a task just for Mormons or the larger Christian community. The Charter For Compassion is a great example of an organization dedicated to the idea of restoring compassion as the root of worship and ethics; exemplifying one way towards achieving radical compassion. Their charter uses the imagery that compassion leads us to dethrone ourselves and place another there:

The principle of compassion lies at the heart of all religious, ethical and spiritual traditions, calling us always to treat all others as we wish to be treated ourselves. Compassion impels us to work tirelessly to alleviate the suffering of our fellow creatures, to dethrone ourselves from the centre of our world and put another there, and to honour the inviolable sanctity of every single human being, treating everybody, without exception, with absolute justice, equity and respect.

The current LDS President elaborated on the essence of charity and its need in this world, in a General Relief Society broadcast in 2010:

There is a serious need for the charity that gives attention to those who are unnoticed, hope to those who are discouraged, aid to those who are afflicted. True charity is love in action. The need for charity is everywhere.

Needed is the charity which refuses to find satisfaction in hearing or in repeating the reports of misfortunes that come to others, unless by so doing, the unfortunate one may be benefited. The American educator and politician Horace Mann once said, ‘To pity distress is but human; to relieve it is godlike.’

Charity is having patience with someone who has let us down. It is resisting the impulse to become offended easily. It is accepting weaknesses and shortcomings. It is accepting people as they truly are. It is looking beyond physical appearances to attributes that will not dim through time. It is resisting the impulse to categorize others.

The expression from the Mormon faith, “except men shall have charity they cannot inherit that place which thou hast prepared in the mansions of thy Father”, is not meant to be merely cute or poetic. And when Christ chose to strike the nerve of hatred between two nations and cultures to illustrate the radical nature of charity, He wasn’t merely trying to be inflammatory. God seems to be warning us that unless we get a handle on this principle of charity and compassion we all face together a very negative future.

This idea is succinctly put by Martin Luther King:

We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.

And from his inspired speech “Loving Your Enemies”, he says:

Now let me hasten to say that Jesus was very serious when he gave this command; he wasn’t playing. He realized that it’s hard to love your enemies. He realized that it’s difficult to love those persons who seek to defeat you, those persons who say evil things about you. He realized that it was painfully hard, pressingly hard. But he wasn’t playing. And we cannot dismiss this passage as just another example of Oriental hyperbole, just a sort of exaggeration to get over the point. This is a basic philosophy of all that we hear coming from the lips of our Master. Because Jesus wasn’t playing; because he was serious. We have the Christian and moral responsibility to seek to discover the meaning of these words, and to discover how we can live out this command, and why we should live by this command.

“Radical compassion” may be a newer term, but the essence of what it is calling for has ancient origins shared across time and cultures. And as we move beyond postmodern attitudes that often dismiss historical and ancient expressions of charity as merely platitudes, we’ll begin to see compassion and charity’s power as a universal truth; one that may ultimately determine our eternal destiny individually and the destiny of mankind with our tools and technologies.